Please note, this is a screening valuation only. This is not a full fledged valuation of the subject shares and therefore should not be used as the final basis for any investment decision.

Prior to performing a detailed valuation on a business, as illustrated in the many examples below, I perform a ‘screening valuation’ of various businesses in order to determine where I should direct my detailed analysis effort. In order to screen businesses I focus on the following elements or numbers of the considered businesses:

• 10 years of Earnings per Share (EPS) data

• 10 years of deflated EPS data

• 10 years of ROE data

• analyst or consensus forecasted EPS growth rate, if available

• lowest P/E ratio over the last 5 to 10 years

• the average Retention Rate (RR) of the business

• the latest available Book Value per Share (BPS)

Using this set of data for each business considered I calculate a number of ratios and returns for each to help me identify potential value investment candidate businesses. Businesses that pass this initial screen will further be analyzed in detail. From the detailed (individual) analyses investment decisions will be made, i.e. the decision as to where investment capital will be allocated.

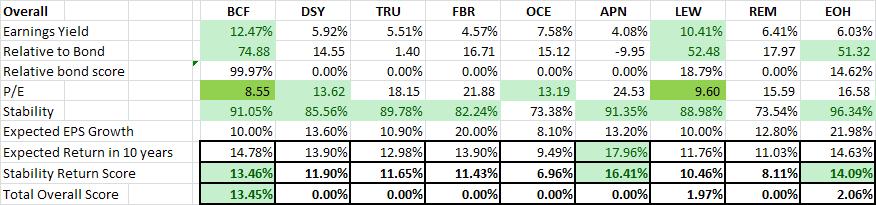

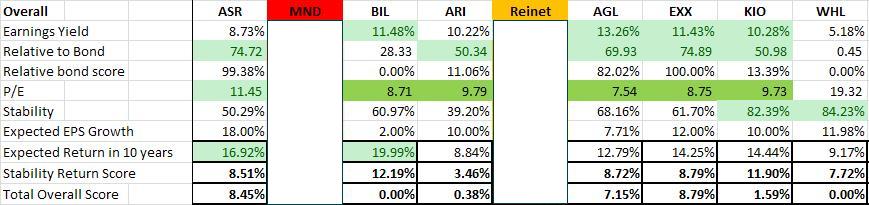

In this post I will be comparing 18 different value stocks as of 28 May 2012. The table below shows the final result of the analysis (I have excluded Mondi and Reinet's screens due to incompleteness of my analysis or incompleteness in the data available). This table shows the result of my screening calculations (not shown in this post) and include 8 overall calculations. Below I have described some of them. They are: - Relative to Bond Yield - I calculate the earnings for a share based on the latest earnings per share (EPS) and current share price (i.e. E/P). I then calculate the historical EPS growth rate and, combined with the analyst expected forecasted EPS, estimate the relative EPS for the next 10 years and possible relative share price in 10 years, if I invested R100 in this business today. I then compare this to the return of R100 invested in a 10 year South African government bond

- Stability Score - I calculate the stability in growth of both the historical EPS and historical Deflated EPS. The stability of growth of Earnings-, Sales- and Book Value per Share are vitally important for any value investor.

- Expected EPS Growth - the expected EPS growth is based on the historical growth rate and the analyst estimate. The expected EPS growth is very conservative to ensure that we rather under-promise and over-deliver than the alternative.

- Expected Return - the compounded annual rate of return is estimated using two different techniques. The first considers the EPS growth over the next 10 years and the second considers the growth in book value over the next 10 years. Both estimate the future share price from these numbers, includes the possible dividends over the next 10 years, and then calculates the expected compound annual return. As can be expected these approaches produce different results, and the final expected return is the average of the two results.

- Stability Return Score - we now come to the crux of the matter. I take the stability score and multiply it with the expected return. This gives me a stability return score, i.e. the expected return impaired for the stability (or instability) of the earnings history. The stability return score forms the basis of the decision whether to further investigate, i.e. perform a detailed analysis of, the business.

- Total Overall Score - I use the stability return score, multiplied by the relative bond score, to calculate the combined effect of the expected return and relative performance to a R100 10 year South African government bond.

The relative ratios and numbers calculated above allow me to screen various possible investments in order to identify the best possible investment candidates. There are a number of other screens not shown here, e.g. price-to-earnings ratio's, price-to-book ratio's, Return on Invested Capital, management screens, competitive advantage screens, etc. My recommendationsI hope you have enjoyed this short valuation example. Based on the above I further analysed (in detail) BHP Billiton. Finally, after the detailed analysis of BHP and other current investment shares, I made my investment recommendations for Richland IH and we will allocate investment capital based on these decisions. A word of warning to anyone contemplating investing in mining shares/commodities: this is a very specialized field and a tenet of any value investor is to remain within his or her circle of competence. Resources are very attractive to value (i.e. long-term) investors, i.e. the world population is growing and although growth in economies speed up and slow down the demand for commodities will just increase in years to come, who are willing to invest in companies with diversified and extensive resource basis (i.e. ore bodies in the ground), that have good management in place, have good distribution networks in place (especially in emerging and high growth markets), are willing to remain invested for the long-term, and fully understand the risks of holding commodity shares (i.e. if they have to sell during a commodity down cycle they will be punished for the decision - commodity companies are price takers not price makers). Please feel free to contact me in case you have any additional questions or suggestions regarding this, or any other, valuation. Always remember to live every day to be a 105%'er ;) Be Extraordinary!

Myles Rennie

P.S. The above analysis should not be considered investment advice. I will not be held liable for any investment decisions, or investments, made based on my analysis.

Valuation Basics - The Financial Statements 1 Before I start my next valuation (it will be done on Assore Limited) I want to spend some time focusing on why and how value investors look at both the Balance Sheet and Income Statement of a company when performing a detailed analysis of a company. OverviewMany people don't like spending time reviewing financial statements. There are many reasons for this, e.g. they might not understand it, it might be too much work, they could be following an investment strategy that does not require study of any financial statements. Unfortunately (or in my case fortunately) the true value investor has to spend time studying these black-and-white pages containing the information required to make good investment decisions. For a value investor the intrinsic value of an investment lies hidden in the financial statements. By gaining a rudimentary understanding of these (easier than expected) documents investors will find that they are not as scary as they first seem. When studying financial statements there are my point to consider. The value investor should consider that: - The balance sheet tells about the firms Assets, Debt and Equity. Assets, the core of most businesses (at least most value investment businesses), can tell about stability, safety, growth potential, and the quality of management. Debt can help firms grow, but increases the riskiness of a business during economic distress. Debt places a burden on earnings and too much of it has lead to the downfall of many businesses.

- The income statement tells about a firms revenue, quality of earnings, sales vs. operational efficiency, has the ability to highlight potential, earnings, and the quality of management.

I will here again repeat Benjamin Graham's definition of an investment: "it is an operation which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative." Safety, in Graham's opinion, is measured in terms of stability based on known information. When valuing stocks (i.e. determining intrinsic value) Graham focused on current information contained in financial statements, and not as much on predicting the future. In a speech in 1975 he is quoted as saying: "I have resolutely turned my back on efforts to predict the future." Intrinsic value is an elusive concept. Ask 10 people to value an asset and you will receive 10 different answers. Value investors have been debating for many years whether to focus on the quality of assets and the balance sheet or whether to focus on the quality of earnings and the income statement to determine intrinsic value. Even the best known value investor of all time, Warren Buffett, has changed his opinion on this matter over the years. In the past he often emphasized the importance of the income statement (for quality earnings and growth) and in recent years he has shifted partially back to assets that can sustain and help a firm in times of recession, inflation, etc. Irving Khan, Graham's teaching assistant at Colombia University, said: "We stress balance sheet and assets. We're old fashioned because our paramount aim is preservation of capital." Walter Schloss, another of Graham's disciples who recently passed away, also emphasized the importance of the balance sheet. These investors all obtained impressive compound annual returns over many years. I prefer a balanced valuation view to include the following three elements: - Existing assets derived from the balance sheet

- Earnings power derived from the income statement

- Growth assets, and related earnings potential, derived from growth assets (determined by reinvestment rates, etc.) on the balance sheet

If a company can present a compelling investment opportunity based on all three investment approaches, then I feel comfortable to consider investing, but only if I can buy at the right price and after passing my Phase I criteria. Balance SheetI like Janet Lowe's analogy of the income statement and balance sheet in her book The Triumph of Value Investing. She says that if a firm was a ship the balance sheet would be the hull and the income statement would be the sails. The hull keeps the business afloat while the sails - propelled by sales - moves it forward. With this analogy in mind, let's start considering what details of a business' hull do we need to check in order to determine whether it will remain afloat. The balance sheet works according to a simple core relationship, and it is: Assets = Liabilities + Shareholder Equity Balance sheets work based on accrual accounting, meaning that revenue and expenses are recognized in the periods in which they are incurred, irrespective of whether cash was involved. It is therefore a statement of financial position, a snapshot of the assets and liabilities at a single point in time. When I start looking at the balance sheet, I focus on five key aspects: - Existing assets

- Growth assets

- Cash, marketable securities and investments

- Debt

- Equity, dividends and retained earnings

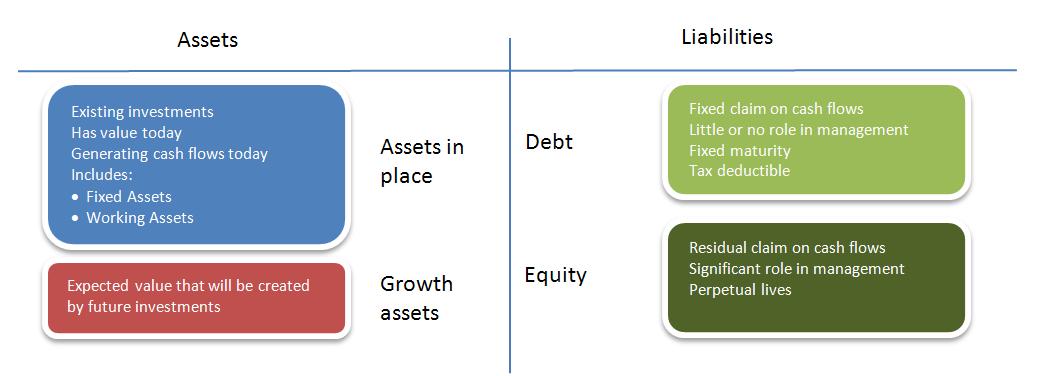

AssetsLet's first consider the difference between existing assets vs. growth assets. Aswath Damodaran, in his book Demodaran on Valuation: Security Analysis for Investment and Corporate Finance, argues that the value of a business could be considered the sum of the values of the individual assets owned by the business, as opposed to the discounted value of all expected future cash flows generated by the assets the business owns. He favours valuing businesses as going concerns, i.e. discounting the conservative future free cash cash flow of the business (generated by assets it already owns and assets it expects to invest in in future) by a risk-adjusted discount factor. To better understand these two 'classes' of assets he proposes visualizing the balance sheet in the form of a 'financial balance sheet' (as opposed to an accounting balance sheet) with investments already made as 'assets in place' and investments we expect to make in the future are 'growth assets'. | | When I do a asset-based valuation, i.e. to determine either book value or replacement asset value, I am focusing only on the existing assets in place and ignore growth assets completely.

| Growth assets only play a role in my growth valuation, performed as the last of three valuation techniques to determine the intrinsic value of a firm (see the image in the section The Value Continuum below). It is clear the picture above that pure asset-based valuations will yield lower values than going concern (or growth) valuations. A couple of brief ideas on assets. Assets are classified as either current or non-current and then there is the distinction between tangible and intangible assets. Current assets are defined as anything that will be turned into cash within 12 months under normal operating conditions. These include cash, cash equivalents, short-term investments, accounts receivable, inventory, and different types of prepaid accounts (e.g. tax). All other assets are non-current assets. Assets can alternatively be classified as tangible or intangible. Tangible assets are sometimes called hard assets and include things like inventory, property, plant, equipment, and cash. All other assets are classified as intangible. CashCash gives a company the ability to weather hard times or take opportunities. On the other hand cash does not earn good returns. Stable cash positions indicates the existence of a durable competitive advantage (in cases where debt levels are consistently low - else debt can be used to smooth cash positions) and eludes to quality, conservative management. Too little cash can constrain the business and stop it from growing or staying afloat. In order to calculate growth assets intrinsic value I will return to cash and specifically the concept of Free Cash Flow, i.e. cash available to the firm or to equity holders after working capital and capital expenditure requirements have been considered. What I would like to say here is that stability in free cash flow, and more specifically positive average free cash flow, is important to the value investor. Free cash flow could be negative for many reasons and could: - signal good things in future, e.g. high growth companies investing more than it is earning

- signal danger, e.g. companies slowly dying and has negative earnings or consuming itself by divesting assets or shrinking capital

- signal possible good returns, e.g. companies that in the past over-invested (capital overspending) and could now benefit from it in the next couple of years

- signal that management might make new stock issues or raise debt (in the case of persistent, even short-term, negative FCFE)

Understanding cash positions, working cash, excess cash, free cash flow, and the application of cash in a company is very important...and a subject on its own. Liabilities and Equity to be discussed in a following post, i.e. Financial Statements 2Typical Asset AdjustmentsPerforming either book value, replacement value, or liquidation value revaluations requires adjustments to the entire balance sheet (assets and liabilities) in order to reflect the economic value of the balance sheet. Typical adjustments include revaluation (mark-to-market) of investments, considering non-operating assets, etc. Please note, and this is very important, that the adjustments made differ for book value calculations vs. replacement asset value calculations! Below is a short list of (typical) asset adjustments: - Marketable securities and short-term investments - determine present market value by marking to market

- Accounts receivable - adjust to net realizable value (book value) or economic value (replacement asset value), e.g. bad debt allowance must either be netted or added

- Inventory consist of raw material, work in progress, and finished goods. If it will be sold in 12 months it will be included in current assets else non-current assets. Adjustments to inventory can be tricky, for instance, if the inventory control system is LIFO and prices are rising then a LIFO reserve (often as high as 20%) has to be added to the inventory asset. To determine any other adjustments to inventory the analyst must determine whether inventory days have been increasing (i.e. inventory turning slower). If it has been increasing then inventory asset value has to be adjusted downward based on the following rules: more commodity type inventory should be adjusted down a little (e.g. down by 25% or 75% of the original value), unsalable inventory should be adjusted down more ( e.g. down by 50% or 50% of the original value), and specialized inventory should be adjusted down the most (e.g. down by 75% or 25% of the original value)

- In the case of replacement asset value prepaid accounts (like deferred taxes), to be 'turned into cash' or 'bartered' within the next 12 months, should be discounted to present value. Using a discount rate of 15% this yields a discount factor of (1/(1+15%)^1=86.95% (i.e. down by 13% or 87% of the original value). In the case of deferred tax assets, it should be offset against any deferred tax liability, and the remaining amount (either asset or liability) should be discounted to its present value (PV) by the appropriate discount rate

- Property, plant and equipment should be considered separately. In the case of a reproduction valuation the historical cost of the different categories of PPE (i.e. property, plant and equipment) have to be considered individually. Property could be estimated based on current market values (or rather fair market values). Plant and equipment could probably be reduced as a result of technical innovation constantly driving down prices (except if plant has recently been replaced)

- Goodwill, when referring to intangible assets used to create value for the firm such as product portfolio, special licenses, customer relationships, competitive advantage, intellectual property, and so on, will probably have to be adjusted upward in order to determine true asset value. However, be careful not to be too optimistic when calculating realistic asset replacement or economic value. It is often not possible to accurately calculate the value of these intangible assets, and here Prof. Bruce Greenwald suggest a shorthand, i.e. use a multiple of the selling, general, and administration (SGA) cost, in most cases between one and three years' worth

- Capitalization of R&D expenses. Often companies expense R&D costs on an annual basis. However, these are actually assets of the company and have to be treated as such. I realize that most value investors shy away from companies with substantial R&D divisions and will therefore never be faced with having to consider capitalizing R&D. For completeness sake, and for situations where needed, I will briefly explain the process here. To capitalize R&D assets we have to start by considering how long it takes, on average, for it to be converted into commercial products. We can take here, as example, five years, which I will consider to be the amortization duration for the asset. Next I have to collect the cost of the expense over the past years ranging back to the amortizable life of the R&D asset. If this cost was uniform then I can calculate the value of the asset as the proportionate sum of the expense over the last five (I chose five as an example) as 1/5 of the cost 5 years ago plus 2/5 of the cost 4 years ago plus 3/5 of the cost 3 years ago plus ... and this years entire R&D expense to arrive at the value of the R&D asset (these are the unamortized amounts of the asset left if assumed that the lifetime is 5 years and the amortization process is linear across the lifetime, which yields 20% per year over 5 years). The effect of book value of equity is therefore: adjusted book value of equity = book value of equity + value of R&D asset. There is however an additional element to consider, and this impacts the Income Statement. The operating income has to be adjusted to consider amortization of the asset instead of the R&D expense. Adjusted operating income = Operating income + R&D expense - Amortization of R&D asset.

- Other adjustments. There are other adjustments than can be made, e.g. financing subsidiaries (e.g. BMW financial services), non-consolidated subsidiaries, prepaid pension assets, etc. These assets must be approached with caution and any adjustments must be carefully considered. In case of doubt, be very conservative and either exclude from the balance sheet or show at low values. In cases where operating expenses (or one of expenses) are capitalized as assets (and subsequent adjustments) care is needed to consider whether the adjustment has a pre-tax or post-tax effect on the Income Statement. Capitalization of pre-tax expenses, like R&D expense, is entirely tax-deductible and therefore no more adjustments are needed. Some companies, like Coca-Cola, could consider capitalize advertising spend because one can argue that it contributed to their brand value. Other companies, like consulting houses, could consider capitalizing recruitment and training fees of their most valuable assets, i.e. people. Amazon could capitalize SGA costs arguing that these expense contribute to brand value and help bring in new long-term customers.

What we are trying to achieve with these adjustments is to be "approximately right rather than precisely wrong". I acknowledge that to value an asset with 100% accuracy is very unlikely, but it is possible to value it within an acceptable margin of safety. These adjustments can be tricky and would be happy to answer any questions about them. Feel free to contact me and I will gladly provide examples and explain them as well. Next Steps (...next posts)

Next I will look at some of the other Balance Sheet items (Liabilities and Equity) and then move on to the Income Statement (for the Earnings Power value) and then the growth assets (for the Discounted Cash Flow valuations).

Please send me your comments or questions. I look forward to hearing from you.

Be Extraordinary!

Myles Rennie

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed